About Free World Blues & Its Authorship

“Look at me. Look into my eyes. I’m the counterculture now.”

Telegram user “Big Sneed” (username identifier withheld in consideration of privacy and absence of consent for disclosure), circa 2022, in reference to, and derivative of, a similar quote by Barkhad Abdi, 2013-09-27. Of note, after sending this message, user “Big Sneed” clarified that, although he was asking a group of anonymous male Telegram users to look into his eyes, he was “not a homo”.

I write nonfiction because my memory is stronger than my imagination: a man should know his strengths and weaknesses, and play to his strengths, no? The adage “truth is stranger than fiction” is an admission of feeble imagination: one can’t claim, in any universal sense, that the finite real events a given man experiences are stranger than the infinite fictitious events he might imagine – it depends on the man, how strange his life, how strong his imagination. Perhaps I have led a particularly eventful waking life, or perhaps my dreams are particularly dull, but the adage holds for me. I am not Gabriel García Márquez; I am not Miguel de Cervantes; I am not Shakespeare; I am not Jules Verne. I accept this.

The great disadvantage of writing nonfiction, in reference to one’s own life, is that it is seldom flattering. Rare are the episodes in my life where I – or my contemporaries – made wonderful decisions at every turn and treated each other with divine respect in every moment. Vanishingly rare are the episodes which are simultaneously examples of perfect moral conduct and actually worth reading about, or worth writing about, for that matter. More than a decade ago, I worked in the San Francisco Bay, and frequently interviewed candidates for roles under my direction. The majority of the questions I asked were technical, but I also wanted to interrogate candidates’ general business sense, so I asked them the following: “Tell me about a company you find interesting“. I soon had to append to this “— specifically, a company other than Tesla or SpaceX” , after more than a dozen Elon Musk fanboys launched into hagiography, which wearied me over the months. The majority of candidates took “interesting” to mean “successful”, and the companies they mentioned were invariably high-profile, generally publicly-traded, and typically in the technology sphere. Alphabet (then Google), Uber, TheFacebook, and AirB&B were all favorites. Cryptocurrency existed at the time, but was far from mainstream and financially worthless, so at least I was salvaged from hearing young men ramble about CoinBase and Yuga Laboratories. The superlative candidate was a young woman who understood intuitively that an interesting business story – one worth studying – need not be a story of brilliant invention, effective marketing, impeccable decision-making, admirable treatment of employees, honest dealings with shareholders, compliance with regulations, and eleven-figure profits. Stories of squandered opportunities, disastrous planning, insidious corruption, large-scale fraud, and financial ruin are as worth studying – if not moreso – than stories of success, and she told me such a story – several, in fact. She had a background in auditing and valuation, having investigated companies to determine their suitability (or, more often, lack thereof) for investment. She understood what no other candidate seemed to: stories of successful companies are amplified by survivorship bias in the Occupation Media, and far more business ventures meet dishonorable ends than become the darlings of Silicon Valley. Hired. As for auditors, so for authors: the stories most worth telling are those of failure, and when I write from my own experience, I’ve plenty of material, but Brother, writing these memories down ain’t easy.

The great advantage of writing nonfiction, in reference to one’s own life, is certainty of what is nonfiction. The events of my life are, by definition, the only events of which I will ever have first-hand experience: I was there, after all. Perhaps I shouldn’t have been there, but there I was. Someone will inevitably ask: “How can you be certain that the events you remember actually happened? Can you prove, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that you are not merely a brain in a vat, overseen by a more-advanced version of Microsoft Tay AI? How can you be sure that you’re not living in a simulation run by concerningly-voyeuristic space aliens? Can you rule out the possibility that you your yourself are an (actual) interstellar alien, your entire life history a hallucinatory vision as you exhale a bong hit of (actual) Kosmic Kush?“. Indeed, I can’t rule out these possibilities with absolute certainty, and I don’t know much about weed culture in the Andromeda Galaxy. Similarly, I can’t rule out, with absolute certainty, the potential that gravity will reverse five minutes from now and fling me into the sky. Yet I choose to trust that physical laws which have existed unchanged for 13.8 billion years will not change next Tuesday, and I choose to trust my own senses, and if I’m wrong about either, I’ll have much larger concerns than discovering that my “nonfiction” was in fact fiction. Indulge me at least this.

“Non-fiction in reference to one’s own life” – Autobiography, then? No – Free World Blues is not an autobiography, nor a memoir. I’m self-indulgent, to be sure, but not that self-indulgent. Not yet. Rather, I share stories of my own life when and where they are relevant. Avoiding self-indulgence is only my third struggle. My second struggle is to find the courage to tell unpleasant stories. My first struggle is to focus on solutions, not problems, for complaining is easy, but does not constitute a path forward. If you pray for me, pray only that hope spring eternal, and within me, and within us all.

Personal Interests

For a minimum of decades, and for a maximum of my entire conscious life, my interests have included the following:

1. Linguistics: Randal Munroe wrote: “I find such joy in language”. I couldn’t have said it better myself; that’s why I quoted him instead. It’s the same reason I call a plumber when a pipe leaks – I’d rather the work be done by an expert. Above all I love grammar; this stereotypically-hated aspect of language learning is in my judgement the most fascinating and beautiful of all. I am particularly interested in comparative linguistics, and the way this science has been used to understand the deep history of nations and peoples, long before genetic analysis was possible. I consider foreign-language learning essential, and hold that raising the level of such study (particularly in the Anglosphere, and double-particularly in America) must be a central goal of national improvement. It is common to meet an American citizen who speaks a language other than English fluently, but in almost all cases this is someone whose first language was not English – typically an immigrant from a non-Anglophone country. Far rarer is the case of a native English speaker who has reached fluency in another language; I estimate the ratio to be at least 10:1 (i.e., English-as-a-Second-Language multilingual Americans outnumber English-as-a-First-Language multilingual Americans by tenfold or more). There are five compelling reasons why foreign-language acquisition is critical; several of these apply particularly to Anglophone people:

I. Uncertainty Regarding The Future Lingua Franca: What’s your chirality? Chirality. Chirality. Handed-ness. Which is your dominant hand? Right? Same with me; we’re the boring ones, right-handed, like most. Roll up your left sleeve, then. You’ll be getting the smallpox vaccine, and we’d rather your left arm be sore for a few days – it won’t interfere with your writing as much that way. The Russians? Chinese? Lab leak? Bioterrorism? No – smallpox is still extinct in the wild in our era, but I’m sending you to 117 AD, Rome. A little sting now, it’ll be well worth it. You’ll need it. Everyone worries about stepping on Julius Caesar’s sandaled foot and getting sent to the Coliseum, but in truth, the greatest danger comes from the smallest of things. A thousand men in every era contracted tuberculosis and died coughing up blood for every one man who met his end in all the battles, sieges, purges, and inquisitions we’ve read about in history books. I’ll be giving you a vaccine for tuberculosis too, and a pack of isoniazid tablets. Take one a day for prophylaxis; take it with food, or it’ll upset your stomach. We don’t want you getting tuberculosis, now, do we? You’ll need your voice in peak form – when you attend your Senate meeting and take the stage, you’ll need to explain to 500 Senators why all this talk about Latin becoming the Lingua Franca is nonsense. These Patricians, you see – their empire spans from Mesopotamia to Egypt, from the Atlantic Ocean to the borders of the Orient, and its 76 million citizens make up more than a fifth of the world’s population. You’ll be visiting the Roman Empire at its peak, when it dominated the world in every dimension: economics, military power, technology, art, literature – everything measurable. For whatever reason, these Patricians think their beloved Latin is destined to become the world language. Your mission is to dispel this arrogant idea. Be sure to let these haughty fellows know that Latin is on its way out, and that the future lingua franca, or at least, the closest thing to it, will be your own native tongue. Let them know that the language destined to displace Latin will be called “English” after the Angles, a Germanic tribe of a few thousand people, hiding out in the swamplands of Schleswig-Holstein (modern-day Northern Germany), after having been driven from more-desirable lands by powerful neighbors. Tell the Romans, in no uncertain terms, that the language of Earth’s greatest empire will be driven to extinction, living on only in Vatican chants and special editions of Harry Potter books for nerds, to be replaced in science, diplomacy, and international communication by the mutterings of some proto-English-speaking swamp savages. This won’t be an easy sell; that’s why you’ll need your voice in top form. You’re headed indoors to the Senate, but use your outdoor voice. Breathe deeply, chest out, shoulders back, stand straight, and – project! In truth, your task is hopeless, or nearly so. No Roman – citizen nor slave, patrician nor plebian – will believe you. The dominance of Latin, in their time, seemed assured. This was neither the first nor last time that a powerful civilization felt certain that their language would become the world language, only to see it displaced, usurped, or even driven extinct. The Persians and later the Arabs of the Middle East, the Egyptians of North Africa, the Bantu of the Horn, the great dynasties of China, the Mughals of India and the Indus River Valley citizens before them, and in Europe the French, the Portuguese, the Germans, and the Dutch – all had their time in the sun. At disparate moments in history, it seemed certain to contemporary men that Farsi, or Arabic, or Demotic, or Swahili, or French, or Sanskrit, or German, or Hindi, would forever be the world language. The empires mentioned showed immense diversity, but had one thing in common: they were all wrong about the “inevitable” dominance of their language. In our time, many Anglophone men (and particularly Americans) seem to think that English will become the world language and remain so for the foreseeable future. These men (or at least those among them who think at all) think they have good reasons for this belief. Perhaps they do, but then again, the Romans thought they had good reasons for their belief – as did so many others. “It’ll be different this time” – the lament of a gambler. Believing that English is certain to be the lingua franca is astoundingly arrogant, and history – fate, if there is such a thing – delights in punishing arrogance. The (lack of) foreign language learning by Americans is strikingly similar to another American mistake: constructing homes, businesses, and infrastructure in the low-lying floodplains of Florida. When the Spanish controlled the region, operating a scheme that was a blend of settlement, proselytizing, crusading, colonization, slavery, indentured servitude, ethnic cleansing, and genocide, the Indians living in the area warned them of the dangers of building in certain areas. The exact warnings were never transcribed, but perhaps the conversation went like this – some Chief said: “How! Pale-Face Siesta Tribe, know this! The land in this area, that area, and over there has a tendency to flood during storms. My tribe live here twelve thousand years, that be one hundred forty-four thousand moons ago, that ancestor first set foot in this land you call Florida. At first we build all over the place, but then flood come, fuck up all our teepees and longhouses, so we learn, where safe to build, where not safe. And the place you Pale-Faces build, it not safe, don’t build stuff there, you retards, it’s going to be swept out to sea!”. The Spanish, of course, thought to themselves “Hmph, these savages don’t know anything, we’ll build wherever we want!”, built structures in the specific areas the Indians warned then not to, and saw mass death and destruction when floods inevitably struck. Willful ignorance of these warnings is especially frustrating because the very issuance of those same warnings was an act of great mercy. In the face of slavery, starvation, and outright extermination by the Spanish, the Indians of Florida had every reason to keep quiet and leave the Spanish to drown in, and from, their own foolishness. But they didn’t. They chose instead to pass on knowledge in an attempt to save lives – the innocent women and children, and the less-innocent alike – of their sworn enemy. To endeavor to save the life of an enemy soldier – while knowing that same soldier thought nothing of slaughtering your civilians – is a flesh-and-blood Act of Grace as great as any the Spanish preached from the pulpits of their mission churches. Certainly the Indians discussed the matter among themselves before deciding to issue warnings; certainly there was vigorous debate, but ultimately, the decision was to show compassion to a people who, by any conventional measure, were undeserving of it. Ultimately, of course, the decision had no effect on outcome, because the Spanish thumbed their noses at their would-be saviors. Two and a half centuries later, the Spanish found themselves being driven from Florida by the Americans, though certainly with less bloodshed than in the previous conflict. This time, the Spanish found mercy within their hearts, and warned the Americans not to build in flood-prone areas, to which the response, in effect, was “Hmph, these Spaniards don’t know anything, we’ll build wherever we want!”. To this day, Americans die in floods as a result of ignoring warnings by two separate civilizations – warnings informed by more than ten millennia of experience in the hydrogeology of Florida. To quote Bill Watterson, “Live and don’t learn – that’s us”. The American who thinks to himself: “Dozens of other peoples over thousands of years have felt certain that their language will be the world language, and all were wrong – but this time, I’m right” is as foolish as the American who thinks to himself: “Dozens of floods have occurred in this area over thousands of years, and people who thought the flooding would never recur have all been wrong – but this time, I’m right”. Communication is important enough that fluency in multiple languages is mandatory – as with all important things, two is one, and one is none.

II. Communication As A Matter Of Safety: Ariseth situations in which rapid, accurate communication – both expressive and receptive – makes the difference between life and death. Typically, this occurs with spoken language, but may occur with written language, as in a situation where reading a warning sign or comprehending a map is critical to survival. The danger may be animate or inanimate. Regarding animate dangers, i.e., dangers posed by other people, there are instances similar to the following: A man is stopped by the police and ordered to raise his hands above his head, but not understanding this, the man reaches into his pocket for his documents – thinking that the officers want to check his identity – and is shot dead for his mistake. Of course, in such cases, though the decedent would have been saved had he been able to understand police orders, there are causes other than linguistic – and, indeed, most accidents have multiple causes and result from a combination of factors, the elimination of any of which would have forestalled the accident. That said, the utility of language is clear. Regarding inanimate dangers (and some animate ones), I recommend that any language learner place a high and early priority on hazard communication. Here are a few phases I suggest, based on my experiences primarily in Russia:

That’s dangerous / that’s hazardous!

Get out of here / get out of there / move there / move here!

Don’t move!

Be quiet; don’t make a sound!

Don’t touch that / stop touching that! / put that down / get away from that!

You will fall!

Get down from there!

That won’t support your weight / that won’t support our weight / that won’t support my weight!

That will collapse!

That’s illegal / that’s a crime!

You will be attacked / you will be bitten / you will be beaten / you will be raped / you will be robbed / you will be cut / you will be shot / you will be killed!

Run!

Hide!

Give chase!

Evade / dodge!

Fight him / fight her / fight them / fight it!

Something is falling / that is falling / that will fall!

A battle is happening / a war is happening / an attack is happening / a riot is happening / a prison break is happening!

Look up / look down / look left / look right / look in front of yourself / look behind yourself!

Don’t eat that / Don’t drink that / don’t breathe that / don’t inject that / don’t insufflate that!

It’s poisonous / it’s infectious / it’s flammable / it’s explosive / it’s radioactive / it’s fissile / it’s dangerously hot / it’s dangerously cold / it’s corrosive / it’s electrified!

There is no oxygen here / You can’t breathe here!

That thing is a threat! / that person is a threat! / that place is a threat!

He is aggressive / she is aggressive / they are aggressive / that animal is aggressive!

He has a gun / he has a bomb / he has a knife / he has a weapon!

There are land mines here / there are land mines there!

A train is coming / a car is coming / a plane is coming / a boat is coming / a motorcycle is coming / a submarine is coming / a vehicle is coming!

Watch out!

I am lost / he is lost / she is lost / they are lost / we are lost / someone is lost!

Oxygen has run out / water has run out / food has run out / medicine has run out!

There is a fire / there is an explosion / there is an irradiation / there is a crash / there is an earthquake / there is a flood!

You will drown / someone is drowning!

We need a doctor / we need a firefighter / we need a search party / we need the police!

I am freezing to death / someone is freezing to death!

These phrases are only a fraction of a fraction of what might suddenly become useful, and for the sake of brevity I haven’t included many medical terms, though of course communicating about diseases, injuries, symptoms, and treatments is important. Nonetheless, I consider learning the above to be a sensible starting point. When I was living in the San Francisco Bay and working at a technology company downtown, my supervisor was very fond of mentioning the “80/20 rule” (also called “the Pareto Principle”, though this term is rarely used in Silicon Valley in my experience, where “80/20” dominates; perhaps it is more common elsewhere). He would make statements along the lines of “80% of our profit comes from 20% of our services“, “80% of our revenue comes from 20% of our users“, “20% of our media spending generates 80% of our sales“, “If we can identify the most important 20% of our codebase, improving that will provide 80% of performance gains“, etc. He would also mention “the 80/20 rule” in a more general sense whenever he wanted to emphasize the importance of prioritization – and, indeed, he was an excellent Founder, planner, and employer by any metric – and, indeed, I agree that prioritization is critical, in business as in any sphere of life. His habit rubbed off on other colleagues, including myself, to the point where it was a common phrase at the Company. Also heard were other percentages which summed to 100: the “90/10 rule”, or even the “99/1 rule”, for situations where someone thought that an even-larger share of outcome was determined by an even-smaller share of input or causality. For example, someone might suggest “The most clueless 1% of our users account for 99% of customer service utilization“. One morning, when he and I were the only ones in the office (early risers, we two), he mentioned the “80/20 rule” yet again. I invited him to join me for a short field trip, and we walked ten meters from the door of our office space to the entrance of the gentlemen’s room in the hallway. A fire extinguisher was mounted by the door. I lifted it from its bracket and cradled it from beneath. “According to my analysis, 99% of fires are extinguished by 1% of fire extinguishers – perhaps we should throw this one away“, I joked. I returned the fire extinguisher carefully to its bracket.

III. A +humility for other speakers

IV. Avoidance of Automated Laziness:

V. Satisfying The Instinct For Communication: Three men meet for dinner. Two of them speak both Swahili and Thai, and the third speaks only Swahili. We would consider it rude – or, at least, potentially rude – for the two bilingual speakers to chat together in Thai while dining with their monolingual, Swahili-only friend. This social sentiment is similar to that against whispering in front of others, as two people speaking in a language only they understand, in the presence of others who lack such understanding, are essentially whispering out loud. This is something I’m often tempted to do, since it offers all the secrecy of whispering with much longer range – in truth, greater secrecy than whispering, because it’s more likely that one will accidentally whisper too loudly and be overheard, than that an eavesdropper who does not speak Russian will suddenly acquire fluency in the language. Like whispering, which excludes others present from a conversation by means of volume, “secret” conversations in a language known only to the speakers and not to others present are a form of exclusion by means of differential knowledge. The fact of the rudeness stems, in my opinion, from a fundamental instinct that humans have to understand language, whether spoken or written or carved in stone. I consider this instinct as fundamental as the desire for food, shelter, sex, water, and air – though not necessarily as strong (no instinct exceeds air hunger in that regard). The portmanteau “Hangry” (“Hungry” + “Angry”) is a perfect description of a man who has become cross because his instinct for food is frustrated. Similarly, we say someone is “sexually frustrated” when that lovely lady or handsome gentleman sadly isn’t interested. In the Pacific Northwest, that jewel of rain and fog, we describe a man who has become wet, cold, and cross as an “unhappy camper”, given that such incidents are common during camping expeditions in the region. I propose a new term, either “Langry” (“Language” + “Angry”, taking after the template “Hangry”) or “Linguistically Frustrated” (taking after “Sexually Frustrated”), to describe a man who is in a bad mood because his instinct for comprehension and communication has been obstructed. The more living languages you learn to speak, understand, read, and write, the less likely you are to become linguistically frustrated, and so language learning is a key to general happiness – both your happiness, and that of those around you, who will be saved from your outbursts of langer.

2. Indian Cultural History: Having visited India, I much hope to return and see more of the Nation. In a sense India is an unlikely country, formed from vastly disparate groups of people, and reminiscent of the United States in that way, with all of America’s quarreling Federalism. India is to me a nation that, for all its faults, has a great deal of interpersonal trust. When visiting, I naturally had to change dollars for rupees, or “Gandhis” as I called them: If I may call hundred USD banknotes “Benjamins”, or USD banknotes more generally “Dead Presidents”, I have every right to call Indian banknotes “Gandhis”, for he adorns all of them, it seems – or, at least, he did when I visited. The most valuable Indian banknote was worth less than 20 USD, and changing several thousand dollars, we ended up with comically massive stacks of Gandhis – credit and debit cards were not common in India at the time, and so cash was our only means of transaction. The bank where we converted our money was a hole-in-the-wall place, where elderly Indian women in colorful saris sat on folding chairs at folding tables, cash-counting machines wired to inverters which were themselves wired to car batteries at the women’s feet. Along with the car batteries, and fully visible sitting open under the folding tables, were moldy cardboard boxes full of cash: Indian currency, hundred-dollar bills, five-hundred-Euro notes. I estimated the value of their cash holdings on the order of $1M – $10M USD equivalent. Here we stood peacefully in line, changed our money, and left – there was no vault, no bulletproof glass, no visible security, no barrier between clients and tellers, and no attempt to conceal the boxes of banknotes on the floor. Perhaps there were plainclothes security officers; perhaps the man behind me in line had an AK-47 folded up in his guitar case, but I doubt it. In a split second I, or anyone else, could have grabbed a box of banknotes and run – I doubt the tellers would have been able to chase me down, for these were some rather hefty ladies, I must say – though nothing wrong with that. Such a casual approach to bearer instruments indicates a society with high interpersonal trust. When making purchases in a foreign country, where there might be a tendency for locals to discriminate against visitors and attempt to rip them off (typically a form of race or national hatred, i.e., adverse treatment of another on the basis of perception of their race or nationality), I take a certain precaution. I make a habit of milling about in whatever store, by whichever market stall, etc. I plan to make a purchase. There, I discreetly observe locals purchasing the same or similar items, watch money changing hands, and get a sense of what the prices are. This method isn’t precise, and won’t allow me to determine if someone is charging me 10% more than they should for a kilogram of salt, but it will allow me to detect massive price-gouging, ex., I will notice if someone tries to over-charge me by a factor of ten. My milling-about strategy was especially easy to apply in India, because commerce was frequent, and though I am short by Western standards, I am tall enough by Indian standards to glance over shoulders and heads with ease. In my travels, I’ve experienced most frequent price-gouging attempts in North Africa. Middle Eastern nations (whether the ostensibly-Jewish nation of Israel, or ostensibly-Muslim nations such as Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey) have intermediate levels of attempted price-gouging, as do Eastern Europe (ex. Russia) and Eurasia (ex. Uzbekistan). Price-gouging attempts are less common in Western Europe, though I’ve certainly encountered such there. India is the only nation where locals dealt perfectly fairly with me, despite my being obviously non-Indian, whereas I could at first glance pass for a local in Europe (East or West) and in much of the Middle East (Jewish or Islamic). Neither was anyone in my party bothered, not men and not women, not when we were together, and not when we were apart. On a limo ride through Mumbai, our driver became lost in a monsoon rain, the downpour so thick it blocked GPS signals, and stopped on a road lined by shacks. He rolled down his window, opened the “maps” app on his iPhone, and handed it to a random young man, dressed in rags, who happened to be treading by. The young man cradled the phone in his left hand, examined the maps, scrolled about a bit, chattered with the driver in a language I could not understand, and then returned the driver his phone, leaving knowledge of the correct route in the driver’s mind, and muddy fingerprints on the driver’s iPhone. It wasn’t as if the driver and man knew each other: this was Mumbai, a city of some twenty-one million, so I can’t imagine that two randomly-chosen men would have more than a vanishingly-small chance of being acquainted, and at the risk of sounding classist, I doubt the man on the side of the road ran in the same social circles as our driver. I do not wish for the land of my birth to “turn into” India, and I’m guilty of having a chuckle or two at “ser, do not redeem” videos, but my time in India left me with an immense respect for a people who have cultivated among themselves a trust that I envy. This is a trust I hope for in my own Nation. My interest in India cowtails well with my interest in linguistics, as it was the Indian scholars of 2,500 BC who composed the Vyākaraṇa, which I consider the dawn of linguistics as a science. At the time, five hundred years before Christ, it was widely believed – especially in Classical Europe – that specific languages were inborn, and in a sense a matter of blood: Roman children were born destined to speak Latin, and Celtic children to speak Celtic, Greeks to speak Greek, and so-on. Indeed, around 430 BC, Herodotus reported on experiments in which children raised without language ostensibly began speaking Phrygian (a Turkic language with similarities to Armenian and Greek), indicating some inborn tendency towards this specific language as a matter of blood. The Ancient Indian author Dakṣiputra Pāṇini called out this nonsense for what it was, and though perhaps not the first to do so (written records being sparse in the Sixth Century BC), he provided volumes of convincing evidence that, although potential for language is innate, specific languages are a matter of learned culture rather than of blood, and a Greek child raised in India would learn Sanskrit just as easily as an Indian child raised in Greece would learn Greek. Languages generally change slowly, such that the splitting of one language into two (or the merging of two languages into one) takes many lifetimes and cannot be observed by a single man due to the brevity of his time on Earth. The Great Vowel Shift that signaled the evolution of Middle English into Modern English took place over the course of four hundred years, so no man living through it was running about on the cobbled streets shouting “The Great Vowel Shift is upon us!”. Like the drift of continents, the rise and erosion of mountains, and the evolution of species, linguistic changes are (generally) gradual enough that they can only be understood through records lasting many lifetimes, and the composers of the great Indian Vedas were the first to keep records of sufficient scope, detail, duration, and accuracy to study these changes rigorously. Particularly impressive

3. Chemical Photography: A man who seeks the best results in a given sphere will achieve the same by using the tools about which he is most knowledgeable. My higher education is in chemistry, and so I practice chemical photography, obtaining better results than I have, or would expect to, with digital photography. A man whose knowledge follows the opposite pattern – a man who knows little of chemistry but is an expert in digital signal processing and silicon wafer fabrication – would naturally obtain better results with digital than chemical photography. My foray began in 2007 when, at an estate sale in Palo Alto, I purchased a Nikon FG and a 50mm f/1.8 Series E lens for a total of 25 USD; the seller initially wanted 50 USD for the lens alone, but I drove a damn hard bargain all those years ago, and I still can if I’m inclined, though I’m less-often so inclined today. This ensemble dated from the early 1980s. I saw terrible results from Kodak Gold 100; I started shooting slide film (E-VI / E-6, or “Ektachrome Six” chemistry, to use a Kodak brand name, though I typically prefer Fuji’s slide emulsions) and saw results closer to what I wanted. From then on, as my friends joke, my journey has been towards ever-less-convenient methods of photography. In 2009, I moved from 35mm to 120 (also called “70mm”, especially in the context of perforated stock used in IMAX cameras) with a Kodak Vollenda from the early- to mid-1930s, purchased at a Palo Alto camera store. The Vollenda was in terrible condition, with so many holes in the bellows that patching it would be impractical; a bellows replacement would have cost far more than the entire camera. I initially cut trapezoidal pieces of leather to create a shade covering the bellows, but still saw light leaks, and so I simply placed the camera in its unfolded position and painted over the bellows with a thick mixture of coal dust and epoxy glue. When this cured, it ensured that the camera could never be folded up again, and certainly destroyed any marginal residual value or beauty it may have had, but finally it was light-tight enough for service. It is well-known that Kodak’s main business activities are wasting investors’ money, destroying stockholders’ equity value, manufacturing dreadful film, harming American industrial competitiveness by snobbishly underestimating the Japanese only to be out-competed by them, and turning Rochester, New York into a Superfund site. Less well-known is that, in addition to these five key (in)competencies, Kodak also has a habit of introducing new and “innovative” film formats, selling cameras in these new formats, coercing laboratories into buying new Kodak-made equipment to process such film, and then discontinuing manufacture of the new format, rendering the cameras and processing equipment it sold useless and worthless, only to come up with a new “innovation” and repeat the cycle. Kodak tried this in the 1990s with disc-shaped film formats, and before that, in the 1980s with APS (“Advanced Photo System”, a process so “advanced” that image quality was worse than that obtainable with film formats produced a century earlier), and before that, in the 1930s, with 620-format film. The Vollenda was chambered for 620-type film, though I didn’t notice this until after I had purchased it, as 620 film is nearly identical to 120 film, except wound on a spool of slightly-smaller diameter with a slightly-narrower axel. Once I discovered this incompatibility, I considered purchasing 620 bobbins and re-winding 120 film onto them in the dark, but settled instead upon cutting down the flanges of 120 spools with a pair of nail clippers, the curvature of whose blades happened to nearly match the curvature radius of 620 film spool flanges. Even better, the nail clippers included a miniature file, which I used to take the edges of the cut flanges down to final size, producing a sufficiently smooth finish in the soft ABS plastic that the spools would spin well enough in the Vollenda to function. I doubt that my cut-down 120 rolls truly met the 620 specifications, but the Vollenda had sloppy-enough manufacturing tolerances that I was able to get away with this. The Vollenda lacked any sort of rangefinder, and with no way to view a scene through the lens with the camera loaded, the method of focusing was to manually measure the distance from film plane to shutter, adjust the focal distance as marked on the lens, and then proceed with manual light metering, exposure calculation, and ultimately the taking of the photograph itself. Although the lens’ focal length was marked clearly in metric with units (105mm), the focal distance was marked numerically, but not with units, leaving me unsure if the units shown were feet or meters. I wasn’t able to find a manual (none was included with the camera and my forays online were fruitless), and so I contacted Kodak customer support repeatedly, both by phone and by email, to ask what I thought was a simple question: Are the focal distance numbers indicative of feet, or of meters? Initially, Kodak support strenuously denied that the Vollenda was even a Kodak product, until I brought them around by sending a link to a page on the George Eastman museum which clearly showed a Kodak-manufactured Vollenda in a display case. Regardless, nobody I spoke to at Kodak support knew whether the markings were in Metric or Imperial units, and so I exposed a test roll, assuming that, since the focal length of the lens was marked in millimeters, the focal distance was likely also Metric. After developing the film at meaningful cost, all my images were severely out-of-focus, as it turned out that the unitless distance markings were in fact in feet, so I had focused far too close (about one-third of the actual distance to the subject) in every case. Of all camera manufacturers, only Kodak would design a camera with the lens focal length listed in Metric units but focal distance calibrated in Imperial units, fail to engrave unit markings on the distance scale, deny having even manufactured the camera while simultaneously showcasing it in their own museum, and then themselves forget which units they used in marking numbers on the scale. Having at least worked out the scale through trial and error on my behalf (emphasis on the latter word), I

***

Note to ID.ME CEO (public letter):

-Point on American law, public defenders only for crimes which could result in death or imprisionment, not for merely fine-able crimes. Hence, loss of liberty (or life) is INHERENTLY more serious than loss of money. A day in prison? Public defender. Million-dollar fine? No public defender required. Cyberattacks are rarely physically dangerous. There are exceptions, ex. StuxNet (though no evidence anyone was physically harmed), and I assume ID.me isn’t running an underground warehouse full of uranium-enrichment centrifuges – though, if ya were, ya wouldn’t tell me, so…I suppose I can’t say for sure. Also, clips from the CEO video – live up to your aspirations.

Cowardice, and hiding behind others. Don’t do it. Take responsibility for your actions, apologize when necessary. Don’t use Customer Service personnel as human shields. That’s fucking cowardly as fuck, bro.

also sought fit to mark the focal length of the lens in metric units (105mm) but marked the rangefinder in Imperial units. Although units (millimeters) were specified on the lens, there were no units on the rangefinder numbers, and so I called and wrote to Kodak’s customer service to determine if the rangefinder markings were in feet

4. Chinese Political History: For example, in the Classical (pre-Medieval, pre-Industrial) era, it was widely believed that language was inborn, a matter of “race” (though this

Pet Peeves

I’m an opinionated man, and my distaste for certain things runs at least as deep as my love for others. Below, I’ve listed my greatest pet peeves. Of note, not every peeve qualifies; I’m annoyed when someone with a handful of coupons holds up the cash register, but this is near-universally disliked, and therefore, while a peeve, it is not a pet peeve. The same can be said for my aversion to music which samples sounds such as ambulance and police sirens, doorbells, ringing phones, and similar. To be a pet peeve, however, a given frustration must be something more or less specific (if not unique) to me, and several indeed are.

1. Improper Maintenance Of Publicly-Visible Timepieces: Whatever property a man possesses, he has a responsibility to prevent from causing harm to others. This applies to movable property: an owner of firearms must securely store the same, such that they don’t fall into the hands of irresponsible parties. This applies to immovable property (real estate): an owner of a pool must fence around it, such that wayward children don’t fall in. I apply this as well to timepieces: Anyone who owns a clock which is in public view must ensure that the clock shows accurate local time, performing maintenance and adjustment as needed. If he cannot or will not do this, he must remove the clock from public view, or at the very least affix a sign informing others that the time shown is incorrect. Of all the Occupation Media babble about “misinformation”, I have yet to hear this issue mentioned once, but it’s caused significant trouble in my personal life. I take a deliberately-expansive interpretation of “public view” to include all cases where a clock is, or might be, visible to someone besides the owner. A clock located in a residence but legible through open windows is “in public view”, even though it is actually located on private property. A clock inside a department store is also “in public view” since such a store is generally open to the public, despite being private property. Finally, a clock in your kitchen is “in public view” if you invite friends over for dinner – what matters is that someone other than you (and, hence, someone who doesn’t know that the time shown is incorrect) might see it.

2. Lovers Not Fully Undressing: To hold a woman, or to hold a man, should be about holding them – not their clothing, not their makeup, not their earrings, but them. Therefore, if you join someone in bed (or on whatever other surface happens to be at hand), you ought to undress completely, or if not completely, as close to completely as reasonably possible. This means removing all clothing, jewelry, and makeup (I consider “makeup” to mean all cosmetics, whether worn by men or women – hence, a man’s hair gel or cologne or deodorant are “makeup” by this standard, and ought to be washed off). In short: If it’s not part of your body, remove it. Set your rings on the nightstand: this isn’t about gold; this is about flesh. “All the world’s a stage” – we can leave Shakespeare to be correct most of the time, but let’s carve out a small exception: let’s agree that all the world is a stage, save for our bedrooms. We humans – we love our gadgets. We’ve loved our gadgets since back when the latest military technology was a bow-and-arrow. We’ve loved our gadgets since back when the latest information-storage technology was a clay tablet paired with a sharpened reed, and I’m certain that, if Silicon Valley tech bros were transported back in time to the Old Kingdom of Egypt, they’d be running about trying to collect startup funding for cutting-edge PI (Papyrus Intelligence) companies. I’m as guilty of this as anyone – more guilty than most, in truth. Technology is in many ways a shield, augmenting our (limited) natural abilities of body and mind. Moments of intimacy should be moments of honesty, where we cast off all this technology, as if to say: Lover, stand before me as you are, your only strength that of your own muscles, your only data-storage that which is behind your eyes – lover, stand before me as I stand before you, with confidence, naked as the day I was born. In my personal life, the woman who doesn’t want to fully undress is usually lacking self-confidence, and so this is the key trait to cultivate: If she doesn’t see her beauty reflected in the mirror, be sure she sees it reflected in your eyes. I’ve learned from private conversations that women are increasingly encountering the same issue with their men. This is unsurprising, given that the body-dysmorphia-industrial-complex has diversified in search of new markets: having focused mainly on shaming women from the Industrial Revolution through the Twentieth Century, it is now expanding out to shame men in the Twenty-First Century, looking to sell ever-more cosmetics and mewing courses. These attempts should be frustrated at every turn. A particular facet of this issue is differential nakedness, typically when a man undresses minimally but expects his woman to undress fully, though the opposite can also occur, and as typical I’ve both committed this transgression and had it committed against me. Nakedness is vulnerability, and expecting your lover to make herself more vulnerable than you when you hold each other is superlatively rude. Like all of my pet peeves, this peeve is subject to reasonable exceptions. If I walk down a public thoroughfare and see a grandfather clock in a private residence showing the wrong time, and the clock is only stopped because it was damaged in artillery shelling, and the clock is only visible from the street through a hole blown into the wall of the man’s residence, I will not fault the owner for improper timepiece maintenance. Similarly, it is perfectly acceptable to keep a bandage or a sling on when holding your lover, or to undress only minimally if you are outside in a severely cold climate. Take your prayers on horseback, as the Muslims say: Islam assigns no shame to a man who misses a prayer for a compelling reason (providing medical care, sailing a ship through a storm, fighting on the battlefield, extinguishing a fire, or otherwise performing a task which must be done urgently to protect human life). A Moroccan barber once told me the following story as he cut my hair in Marrakesh. This story is potentially heretical, possibly apocryphal, likely ahistorical, and certainly anti-Jewish, but I shall tell it as he told it to me, translating it from the French in which we spoke to English in a sensible way:

A Jewish merchant sold qibla compasses to the Muslims of Casablanca, so that they would know which way to face towards Mecca during their prayers. One day, the Jew came to the mosque, stood before the Muslims, and shouted: “Oh Muslims, I have tricked you! The Hajj compasses I sold you were miscalibrated, such that you have prayed in exactly the wrong direction, with your asses towards Mecca. Yes, all this time, you’ve been showing your asses to Allah. Surely He will condemn you to the Hellfire!”. The Muslims determined that the Jew had spoken the truth: the compasses were indeed pointing in exactly the opposite direction as they should have, and they had indeed been praying with their rear ends towards the Kaaba. They rushed to their Imam, worried for their souls in the Ever-After. The Imam told them this: “Our God is not a hateful God. He will not fault you for innocent mistakes, or the consequences of the malice of others. On the Day of Judgement, he will not be examining every prayer of your life and measuring the direction you were facing with a protractor, counting how many degrees you were mistaken by, in order to condemn you to the Hellfire. Our God is, simply put, not like that.”

Nor am I. Without claiming any specific knowledge of Islam, without commenting on whether these events actually happened (I can find no evidence that they did), and not being Muslim myself, I do approve of the sentiment of understanding held within the story.

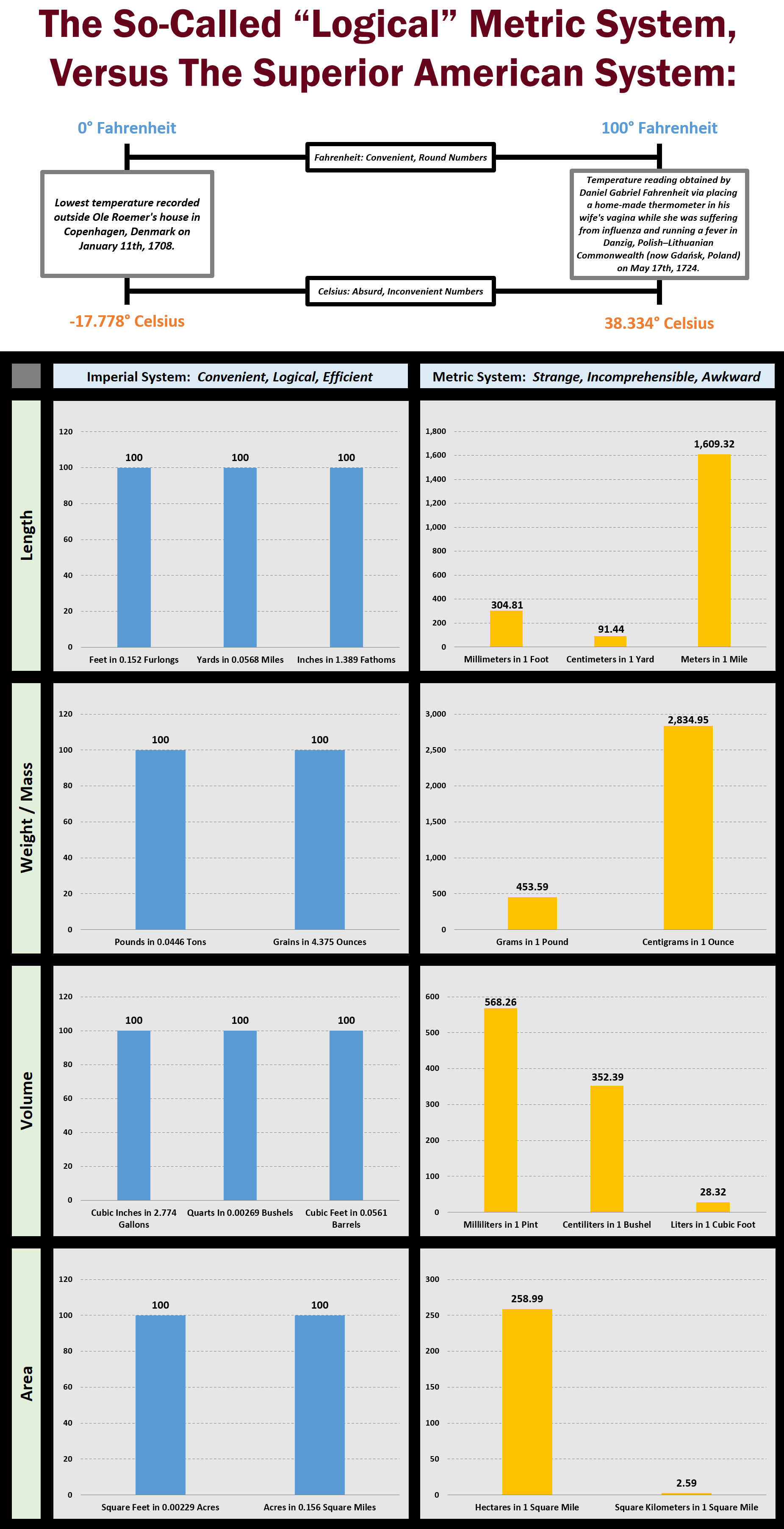

3. Irrational Resistance To Standardization, And Particularly, The Practice Of Unit-Mixing: On the foggy morning of 1940-06-23, Adolph Hitler stood on low steps above the Champs-Élysées, la Tour Eiffel in the background. A photograph of this moment, in black-and-white, celebrating the victory of the Black and White and Red over a conquered France, is an icon of the War. The French suffered greatly in defeat and occupation, losing some 200,000 soldiers in battle, and twice that number of non-combatants, for a total toll exceeding 600,000. Civilians were worked to death in labor camps, executed for political dissent, subjected to genocide, starved in sieges, incinerated in aerial bombings, and otherwise met their ends by the hundreds of thousands as a consequence of the conflict. This second World War, itself part of a trilogy incomplete as of the date of this writing, was far from the first Franco-German conflict: the French and Germans inflicted at least greater military (if not civilian) losses upon each other in the First World War. This “War to End All Wars” (as poorly-named as “Her Majesty’s Honorable British East India Company”) was itself predated by the Franco-Prussian War in the early 1870s, which itself was predated by clashes in the Napoleonic Wars. Before even Napoleon, the French and Germans (or, at least, proto-French and proto-Germans) clashed in the Seven Years’ War of the 1750s – 1760s, and before that, in the Thirty Years’ War of the 1610s – 1640s. It suffices to say that the Germans and French have as much of a history of shed blood as any two peoples, races, nations, or civilizations ever did. On 1951-04-18, five years to the day after end of World War II in Europe, French and German diplomats signed the articles of the European Coal & Steel Community, each agreeing to waive tariffs on these vital industrial commodities as traded between the two Nations. The European Coal & Steel Community grew over the following years into what is now the European Union, with France and Germany accepting each other’s driver’s licenses as of 1991-07-29. Despite centuries of bloodshed, millions of shallow graves, the advent of chemical warfare, and atrocities ranked among the worst in human history, a Frenchman who as a child saw Hitler strolling through Paris can drive in Germany indefinitely with a French driver’s license, and a German who as a child was coerced into the Hitler Youth can likewise drive in France indefinitely with a German driver’s license. Meanwhile, when I moved from Seattle to San Francisco for University, I was stopped on the 101 and fined $480 for not having switched my Washington driver’s license to a California driver’s license after 30 days of presence in California. France and Germany – at war on and off since the Sixteenth Century – have somehow managed to set their differences aside to achieve standardization of driver’s licenses, and in fact they accomplished this more than three decades ago. Washington and California – two divisions of the same Nation, never having borne arms against each other – have somehow failed to achieve the same. This is despite the fact that Washington and California are strongly politically-aligned, the Democratic Party being dominant in each. The situation is, of course, no better with U.S. States that are politically-aligned to the Republican Party: Texas and Florida won’t accept each other’s driver’s licenses either; nor will South Carolina and North Carolina, despite these sister states being GOP strongholds and sharing an internal border. In 2019, a colleague of mine posted in an off-topic Slack channel about exactly the frustration of needing to get a new driver’s license when moving from South Carolina to North Carolina, and I replied to the thread with that stark black-and-white image of the Führer in Paris. My supervisor immediately chimed in, demanding I explain myself, implying that my posting of the image – one of Hitler in a moment of triumph – was a promotion of the Third Reich. I had to explain to him – and to the others in the thread – that I meant nothing of the sort: The photograph, when considered in combination with the Franco-German relationship in the continuing post-War period, is a representation of how old foes can overcome vast differences to make life easier for the Common Man, and an indictment of Americans for failing to overcome comparatively-minor differences in the name of the same. My supervisor calmed down, but told me I should have sent the image with context: an absurd demand, considering that the “context” is one we all share, if we make an effort to educate ourselves. The post-War history of Europe is hardly secret knowledge known only to me, and is the subject of kilometers of bookshelves in any University library, but if a man wants to bury his head in the sands of La Plage de Normandie, I can’t stop him. Troubles with driver’s licenses are only a minor part of this pet peeve: differences in laws and licensing requirements between different U.S. States create an enormous barrier to doing business nationally, prop up fifty smaller agencies when one larger National agency could likely accomplish the same with less cost and redundancy, and overall create a headache. National agreement and compromise (resulting, for example, in a National firearms law neither as strict as California’s nor as liberal as Texas’, and a National drug law neither as liberal as Washington’s nor as strict as Utah’s) would provide net benefit, in my judgement. I do not entirely dismiss arguments for customized State-level laws; I consider these arguments to be valid, but greatly outweighed by the benefits of standardization. Aside from legal standardization within the Nation, American and foreign (particularly, Russian) resistance to international standards in weights and measures frustrates me. On a trip from PSP to VKO (the entire itinerary being PSP → JFK → CDG → VKO), I missed my entire series of flights – delaying my travel by some 30 hours – as a result of a unit-conversion error made by the staff of Palm Springs International Airport. Some background is of note. I agree with almost nothing that the US Department of State says about Russia. For example, urban Russia is vastly safer than urban America, despite the DoS issuing a “Do Not Travel – Depart Immediately” warning for Russia; similarly, the overwhelming majority of Americans who are in legal trouble in Russia have only themselves to blame, and are not subject to any sort of National or political persecution, despite the DoS warning Americans of “targeted harassment” by the Russian State. The Department of State also warns against travel to Russia because US credit cards do not work there; this is true, but more curiously, is an example of the United States government warning about a problem that it, itself, has created. However, one quote from the Department of State is whole truth: “Russian authorities strictly enforce a complex set of visa and immigration laws”. Russia is second only to the United States in volume of illegal immigration, and at the time of this incident (laws may have become stricter or more lax since), Russia assessed a penalty of approximately $40,000 for appearance at a border checkpoint without a visa, ВНЖ, or other valid entry document. An identical fine is enforced on carriers. Hence, if someone without a visa or other entry authorization arrives at the Russian border, he will be fined ~$40,000, as will the operator of the vehicle (be it an aircraft, ship, train, or bus) that delivered him, assuming the unauthorized person did not arrive on-foot or in his own vehicle, in which case only the first fine (that applied to the unauthorized attempted entrant) will be in force. The fine assessed on vehicle operators is per unauthorized entrant; hence, if a flight lands in Внyково with 5 Americans onboard who lack valid entry documents, each of those entrants will be fined ~$40,000, and the operator of the flight will be fined (5) * (~$40,000) = ~$200,000. Unauthorized attempted entrants are incarcerated until their fines are paid, and then sent home at their own expense. Similarly, pilots and crew (of aircraft or ships), and drivers and conductors (of busses and trains), are incarcerated pending payment of fines, and the vehicles in question are impounded and may be confiscated and sold by the Таможенние (Сustoms Enforcement) or Росгвардия (Border Guard) in order to pay off carrier fines. Given that the long-haul aircraft used for flights into Moscow have a price tag of several hundred million dollars, and given the desire to avoid having pilots and crew incarcerated abroad, commercial air carriers are extraordinarily careful to ensure that all foreigners en route to Russia have correct travel documents. At the point of departure for a series of flights ending in Russia, carriers go beyond merely examining visas, and in fact check with the Russian embassy in the departure jurisdiction to ensure the documents are valid. The Russian mission to the United States offers a web interface for these checks, requiring the following inputs to look up a visa record:

Traveler First Name: [Latin alpha, ex. “John”]

Traveler Last Name: [Latin alpha, ex. “Doe”]

Traveler Nationality: [ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 code, ex. “US”, “FR”, “IN” for the United States, France, and India, respectively]

Traveler Passport Identifier: [Latin alphanumeric, ex. “Z84757391”; often called a “Passport Number” despite being alphanumeric]

Traveler Date of Birth: [dd/mm/yyyy = дд/мм/гггг]

Traveler Date of Passport Issuance: [dd/mm/yyyy = дд/мм/гггг]

Traveler Date of Passport Expiration: [dd/mm/yyyy = дд/мм/гггг]

Visa Transliteration of Given Name: [Cyrillic alpha, ex. “Владимир”]

Visa Transliteration of Patronymic: [Cyrillic alpha, ex. “Владимирович”]

Visa Transliteration of Family Name: [Cyrillic alpha, ex. “Путин”]

Visa Date of Issuance: [dd/mm/yyyy = дд/мм/гггг]

Visa Date of Expiration: [dd/mm/yyyy = дд/мм/гггг]

Visa Number: [Numeric, ##-#######]

Critically, this service of the Russian Embassy to America returns only a YES/NO answer; if all the input data exactly match a record in the Embassy’s database of valid visas, a “VALID” response is returned; otherwise “INVALID” is returned. There is no way to perform a partial search, i.e., there is no way to view all valid visas issued to men named “John” who were born on September 14th, 1990, or to browse through visas generally. Such precautions make sense, as they’re necessary to prevent browsing of visa information, which capability would be useful to counterfeiters. However, this website behavior means that determining the validity of a visa requires every field to be entered exactly correctly. The issue in my case was the date format, and specifically, the date format as it applied to my date of birth and the issuance and expiry dates of my American passport. The US conventionally uses the [mm/dd/yyyy = мм/дд/гггг] format (month / day / year), whereas Russia uses the [dd/mm/yyyy = дд/мм/гггг] format (day / month / year). In short, the staff at Palm Springs were ignorant of this, and did not swap the month and day when entering my passport data into the Russian Embassy system, leading to a spurious “INVALID” result, which caused them to refuse me boarding. I had previously flown to Russia multiple times on various visas without issue, mainly from SEA and SFO, but this is because these origin airports are staffed by competent men and women who are aware of Russian date formats and visa verification processes (and presumably, the date formats and visa types issued by the other 194 countries on Earth). The same, sadly, cannot be said for employees of PSP. By the time they had identified the error and explained it to me, six hours had passed and I had missed my series of flights, and so had to stay in Palm Springs for an additional night at my own expense, though the new flights were provided free of additional charge. I hadn’t thought to explain the matter of date formats to the airport staff myself, since I had never encountered the problem before, given my uneventful travels from other origin airports. As with most incidents, there’s plenty of blame to go around. Part of the blame falls on the staff of PSP, for not knowing how to check the validity of Russian visas, which any employee at an international airport ought to. Part of the blame falls on the IT team of the Russian Mission to America, who could have explained date formats more clearly and prominently on their web interface. Indeed, I’ve found the following meme to be true regarding Government websites of all nations (notably having had experience with products of the United States, France, Russia, Morocco, India, Thailand, Uzbekistan, and Turkey):

Regardless of how the blame might be apportioned between myself, Russian web developers, and American airport employees, this incident could easily have been avoided if Russia and the United States (and all other Nations) adopted the ISO 8601 date format. This format prescribes a [YYYY-MM-DD = ГГГГ-ММ-ДД] format, ex. the first Moon Landing occurred 1969-07-20, or July 20th, 1969. This standard is already near-universal within computing, and in that way I’ve had most of my contact with it, particularly in database work. The year-month-day order is logical in the sense that it puts the largest units (the most significant figures) first, with figures descending in significance from left to right. We say “three hundred twenty-six”, mentioning first the hundreds’ place, then the tens’ place, then the ones’ place. The current Russian date standard is equivalent to saying “six, twenty, and three hundred” (exactly in reverse order, i.e., small-medium-large), and the current American standard is equivalent to saying “twenty, six, and three hundred” (an even more-jumbled order, i.e., medium-small-large). I wouldn’t describe my height as “five inches and five feet” (the Russian order), or the length of a road as “Twenty feet, seven inches, and three miles” (the American order), so I fail to understand why this absurdity should prevail for dates. Russians and Americans should be especially keen on unit standardization, having both suffered national embarrassments due to conversion issues: the Russian Olympic team once arrived too late to compete at the Games in London due to failure to convert Julian calendar dates to the Gregorian calendar, and the American space agency NASA crashed a spacecraft into Mars (unmanned, fortunately) due to failure to convert pounds (lbs) into newtons. Though hardly as impactful as these incidents, the greatest absurdity I’ve encountered is when, in Oakland, the concentration of a chemical in a mixture was described to me in “milligrams per ounce”, mixing Système International with Imperial units. I do understand why this absurdity does prevail, at least for the moment. Part of the issue is a sense of patriotism in “our” system of weights and measures. Often this patriotism is misplaced, as when Americans become “patriotic” about the Imperial System, despite the reality that (1) the Imperial System is not an American invention; (2) the Imperial System was inherited from the British, the very imperialists which America fought and defeated in the Revolutionary War to gain independence; (3) The Système International, which Americans “patriotically” reject, was invented by the French, by far our most important ally in the Revolution. Only an American politician could argue that rejecting an objectively-superior system created by our greatest ally in favor of an objectively-inferior system created by our greatest enemy is “patriotic”, given that this claim is wrong thrice: yet somehow this is far from the most nonsensical aspect of American politics. The primary cause of unit chaos is not patriotism, but short-term thinking. It is short-term thinking that leads Nations to reject the significant long-term benefits of standardization in favor of avoiding the comparatively-minor short-term costs of replacing speed limit signs and reprinting calendars. It is short-term thinking that has been the scourge of my life and that has so often made me a scourge onto others. It is short-term thinking, above all else, that I aim to challenge in my writing. We are destined to overcome short-term thinking, and when we do, unit-standardization will be the most diminutive achievement, hardly worth mentioning alongside greater victories. Until then, I’ll treat the Germans I meet in the ghetto of the Internet to the following, a little creation of mine: